在这里分享并记录一些零散的想法及写作。

2021/02/15 Daily Readings

- What are the most important statistical ideas of the past 50 years? https://arxiv.org/pdf/2012.00174.pdf

2021/02/14 Big Changes in Go 1.17

Runtime changes:

- New GC Pacer: https://golang.org/issue/44167

- Scheduler performance: https://golang.org/issue/43997

Toolchain changes:

- Register-based calling convention: https://golang.org/issue/40724

- Fuzzing: golang.org/s/draft-fuzzing-design

2021/02/10 A New GC Pacer

今天,Go 团队发布了一个全新的 GC 的调步器(Pacer)设计。这次就来简单聊一聊这个以前的设计有什么问题,新的设计又旨在解决什么问题。

目前 Go 运行时的 GC 是一个并发标记清理的回收器,这涉及两个需要解决的核心问题:1)何时启动 GC 并启动多少数量的 worker 进行搜集从而防止回收器使用过多的计算资源影响用户代码的高效执行;2)如何防止收集垃圾的速度慢于内存分配的速度。

为解决这些问题,早在 1.5,Go 团队将这个问题视作一个最小化堆的增长速率和 CPU 的使用率的优化问题,从而促成了两个关键组件:1)调步器:根据堆的增长速度来预测 GC 的触发时机;2)标记助理 (Mark Assist):暂停分配速度过快的用户代码,将正在分配内存的用户代码转去执行垃圾标记的工作,以便顺利完成当前的 GC 周期。

然而这样的 GC 在实施调步决策时,包含一个隐藏的假设:分配速率总是一个常数(1+GOGC/100),可惜由于标记助理的存在、实现与理论模型的差异,导致这个假设其实并不正确。进而带来的很难解决的问题:1)当分配速率违反常数假设时,预测的启动时间太晚反而需要消耗过多的 CPU,虽然可以动态的调整 GOGC,但这仍然是一个超参数,人工优化需要大量的领域经验,很难直观的使用这个变量对 GC 进行优化;2)由于优化问题是以堆的增长为目标,由于没有堆内存大小的使用限制,无论是设置过大的 GOGC 或者出现峰值分配时都会导致堆的迅速增长从而 OOM;3)在当前 GC 周期内新分配的内存将留到下一个 GC 周期进行回收,标记助理暂缓分配带来的延迟停顿 STW;4)… 那么新的调步器为解决这些问题做了什么重新设计呢?

正如前面所说,产生各类问题的主要来源是对分配速率为常数这一错误的假设,那么自然也就很容易想到在建模的过程:利用标记助理这一组件来动态的计算分配的速率,从而达到动态调整堆目标的目的。可惜的是原来的设计中标记助理仅统计了堆上的分配情况,而对栈或全局变量没有加以考虑。为了让问题考虑得更加全面,新设计中引入了一个「辅助率」,表示当前 GC 周期新产生但没有回收的分配量(A)与当前 GC 周期完成的扫描量(B)之比,A/B。这一指标更加直观的反应了 GC 的实际工作难度:如果用户分配速率过高,那么 A 将增大,进而辅助率增高,需要助理提供更多的辅助;如果分配速率适中,辅助率下降。根据辅助率的引入,调步器便可动态的的调整助理的辅助工作,进而解决辅助时带来的停顿。

我们来看一个实际的场景:当突然出现大量峰值请求时,goroutine数量大量增加,从而产生大量栈和分配任务,极其模拟的结果:图 1 是调整前的调步器,图 2 是调整后的调步器。可见图1左下角显示,总是错误的低估了堆目标工作量,导致堆总是在过冲;而新的调步器能很快的收敛到零,完成堆目标的预测;图 1 右上角则表明实际的 GC CPU 使用率总是比目标使用率低,从而为能完成预期指标;而新设计的调步器则能很快收敛到目标的 CPU 使用率。

当然,限于篇幅上面只是对新的调步器设计做了一个非常简略的介绍。如果对这个内容感兴趣,可以查阅后面的这些链接,之后有机会再对此设计做进一步详细的分享。

- GC 调步器现存的问题:https://golang.org/issue/42430

- 新调步器的设计文档:https://go.googlesource.com/proposal/+/a216b56e743c5b6b300b3ef1673ee62684b5b63b/design/44167-gc-pacer-redesign.md

- 相关的提案:https://golang.org/issue/44167

- GC 新调步器模型的模拟器:https://github.com/mknyszek/pacer-model

2021/01/27 Go 1.16 Big Changes

Go 1.16 发布了非常多非常有趣的变,尝试做一个简单的总结:

russ cos: deprecated.

- https://twitter.com/_rsc/status/1351676094664110082

- https://go-review.googlesource.com/c/go/+/285378

- https://github.com/golang/go/issues/43724

- 支持 darwin/arm64

- 支持 darwin/arm64 上遇到的问题

- 苹果的bug: 与信号抢占有关

- Apple Silicon M1 性能

- 但是在加密上性能很差

- 发版周期:https://github.com/golang/go/wiki/Go-Release-Cycle

- 编译器自举过程

- 支持 darwin/arm64 上遇到的问题

-

安装 Go:https://gist.github.com/Dids/dbe6356377e2a0b0dc8eacb0101dc3a7

-

https://github.com/golang/go/issues/42684

- 内核恐慌的第 62 期:你的电脑不是你的,代码签名,OCSP Server

- ken thompson 图灵奖演讲:reflections on trusting trust

- TODO

- 苹果代码签名的老问题,早年做 electron 也是这类问题,现在这样的问题还是存在

-

异步抢占随机崩溃,是 Rosetta 的 Bug:https://github.com/golang/go/issues/42700

-

自居,安装的困惑:https://github.com/golang/go/issues/38485#issuecomment-735360572

- Go 语言的自举分为三个步骤

-

- 1.4 C version TODO

-

- tool chain 1

-

- tool chain 2

-

- tool chain 3

-

- Go 语言的自举分为三个步骤

-

在 Rosetta 下运行 x86 程序:

arch --x86_64 -

dotfiles 中关于 M1 的兼容性情况:https://github.com/changkun/dotfiles/issues/2

-

十二月初入手 如今已经使用快两个月了 非常流畅 续航逆天

-

我的必备第三方软件列表:

- homebrew (支持性不好,好在现在大部分依赖的软件是用 Go 写的,而且 Go 的支持非常完善)

- 不考虑兼容性 随意破坏兼容性移除软件分发,有一个 rmtrash 的工具,我从2014年左右就开始使用,但是去年被从软件分发中移除了,所以自己写了一个全兼容的工具changkun.de/s/rmtrash,但没有被合并,他们说了要被原软件作者任何才能不受受欢迎程度的限制,但实际上软件作者已经联系不到了

- vscode(已在长期使用 Insider)

- macvim

- tmux

- oh-my-zsh

- Blender(Cycles 光追渲染不支持 GPU,但编辑顶点小于百万级别的网格是没有问题的)

- iTerm:支持 M1

- Chrome:支持 M1

- MacTex:支持 M1

- Docker:圣诞节前一周发布支持,很完美,至今没有遇到问题

- homebrew (支持性不好,好在现在大部分依赖的软件是用 Go 写的,而且 Go 的支持非常完善)

-

Go Modules 的变更

- 收集反馈

- 复杂依赖管理,你实践中管理过最复杂的项目依赖多少模块,每次依赖升级都有写什么?在没有 Go modules 之前你用的是什么?

- 我的经历:Go vendor, 1.10 dep, 1.11 go modules,

- GOPATH 的项目管理,现在虽然移除了 gopath,但我还是沿用了 gopath 的习惯

- 最小版本选择

- Semantic Versioning: major.minor.patch

- 经典的钻石依赖问题:A依赖B和C,BC分别依赖 D 的不同版本,而这两个版本的 D 不兼容,所以无法在依赖中选取一个特定的D版本,semantic import versioning 消除了这种依赖,在import path的最后添加了主版本号的要求/v2

- dep 不允许钻石依赖,升级非常难

- 构建的可重复性,没有lock文件,>=的依赖会随着时间的变化而变化

- 选择最小的可以依赖的版本,构建不会随时间的变化而变化

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F8nrpe0XWRg&ab_channel=SingaporeGophers

- 不被理解的工作方式

- GOPATH

- vendor

- 三大要点

- 兼容性

- 可重复性

- 合作(通常被很多人忽略)

- 默认启用 Go Moduels, go build 必须包含 go.mod 文件,否则编译失败

- build/test 不会升级 modules

- 默认 -mod=vendor

-

文件系统接口

-

fs.FS 抽象的重要性在哪里

- unix file system abstract always disk blocks

- network file systems (upspin) abstract away machines

- rest abstract nearly anything

- cp 不关心是否移动文件的区块,甚至不关心文件在哪个位置,可能是不同的磁盘也可能是不同的机器

- 定义任何文件类型工具的「泛型」

-

导致了哪些主要变化

- io/ioutil

- Russ cox 对 deprecated 在 go 中的解释(https://twitter.com/_rsc/status/1351676094664110082)

- https://www.srcbeat.com/2021/01/golang-ioutil-deprecated/

- 其他 fs 的抽象

- Rob Pike 的 2016/2017 Gopherfest, Upspin、Changkun 的 Midgard

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ENLWEfi0Tkg&ab_channel=TheGoProgrammingLanguage

- FUSE: filesystem in userspace

- https://changkun.de/s/midgard

- every user has a private root, no global root,

r@golang.org/some/stuff, user names look like email address - access control defined by plain text files

read: r@golang.org, ann@example.com

- 目前的非常简单的实现,只是一个只读文件系统

- ReadDir and DirEntry

- 可扩展的方向:memoryFS,支持回写到磁盘、hashFS 为 CDN 提供支持

- 还存在的问题。。例如 44166

1 2 3 4 5 6 7import _ "embed" //go:embed a.txt var s string import "embed" type embed.String string var s embed.String1 - io/ioutil

-

-

文件嵌入 //go:embed

- 新特性的基本功能

- 一些可能的应用

- 一些在feature freeze cycle 中才讨论出来的feature

- https://blog.carlmjohnson.net/post/2021/how-to-use-go-embed/

-

运行时内存管理

- 回归 MADV_DONTNEED

- 新的监控基础设施 runtime/metrics

- 以前的监控函数:runtime.ReadMemStats, debug.GCStats,

- runtime/metrics:

- metrics.All()

- Issue 37112

|

|

- 其他值得一提的特性

- os/signal.NotifyContext

- 内存模型修复

- 链接器优化

2021/01/18 Daily Reading

- What to expect when monitoring memory usage for modern Go applications. https://www.bwplotka.dev/2019/golang-memory-monitoring/

- Distributed Systems. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UEAMfLPZZhE

- Golang News. https://www.golangnews.com/

- SIGCHI Symposium on Engineering Interactive Computing Systems. http://eics.acm.org/

- runtime: use MADV_FREE on Linux if available https://go-review.googlesource.com/c/go/+/135395/

- runtime: make the page allocator scale https://github.com/golang/go/issues/35112

- runtime: add per-p mspan cache https://go-review.googlesource.com/c/go/+/196642

- A New Smoothing Algorithm for Quadrilateral and Hexahedral Meshes. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F11758525_32.pdf

- OpenGL Docs. https://docs.gl

- On Playing Chess. https://blog.gardeviance.org/2018/03/on-playing-chess.html

- Memory Models: A Case For Rethinking Parallel Languages and Hardware. https://cacm.acm.org/magazines/2010/8/96610-memory-models-a-case-for-rethinking-parallel-languages-and-hardware/fulltext

- Engineer level & competency framework. https://github.com/spring2go/engineer_competency_framework

- A Concurrent Window System. http://doc.cat-v.org/bell_labs/concurrent_window_system/concurrent_window_system.pdf

2021/01/06 Creating A Window

如何使用 Go 创建一个窗口?macOS 有 Cocoa、Linux 有 X11,但访问这些 API 似乎都需要 引入 Cgo,可不可以不实用 Cgo?一些现有的 GUI 库或这图形引擎:

GUI 工具包:

- https://github.com/hajimehoshi/ebiten

- https://github.com/gioui/gio

- https://github.com/fyne-io/fyne

- https://github.com/g3n/engine

- https://github.com/goki/gi

- https://github.com/peterhellberg/gfx

- https://golang.org/x/exp/shiny

2D/3D 图形相关:

- https://github.com/llgcode/draw2d

- https://github.com/fogleman/gg

- https://github.com/ajstarks/svgo

- https://github.com/BurntSushi/graphics-go

- https://github.com/azul3d/engine

- https://github.com/KorokEngine/Korok

- https://github.com/EngoEngine/engo/

- http://mumax.github.io/

这里有一小部分:

https://github.com/avelino/awesome-go#gui

大部分人的做法是使用 glfw 和 OpenGL,这是一些需要使用到的库(Cgo 绑定):

这里面有一些相对底层一些的,比如 X 相关:

- X 绑定:https://github.com/BurntSushi/xgb

- X 窗口管理:https://github.com/BurntSushi/wingo

比如 macOS 上如果需要用到 Metal:

像是前面的 GUI 工具中的 ebiten,在 windows 上已经不需要 Cgo 了,做法似乎是将窗口管理相关的 DLL 直接打包进二进制,然后走 DLL 动态链接调用。

除了 GLFW 之外,还有相对重一些的 SDL:

一些基本名词之间的关系:

|

|

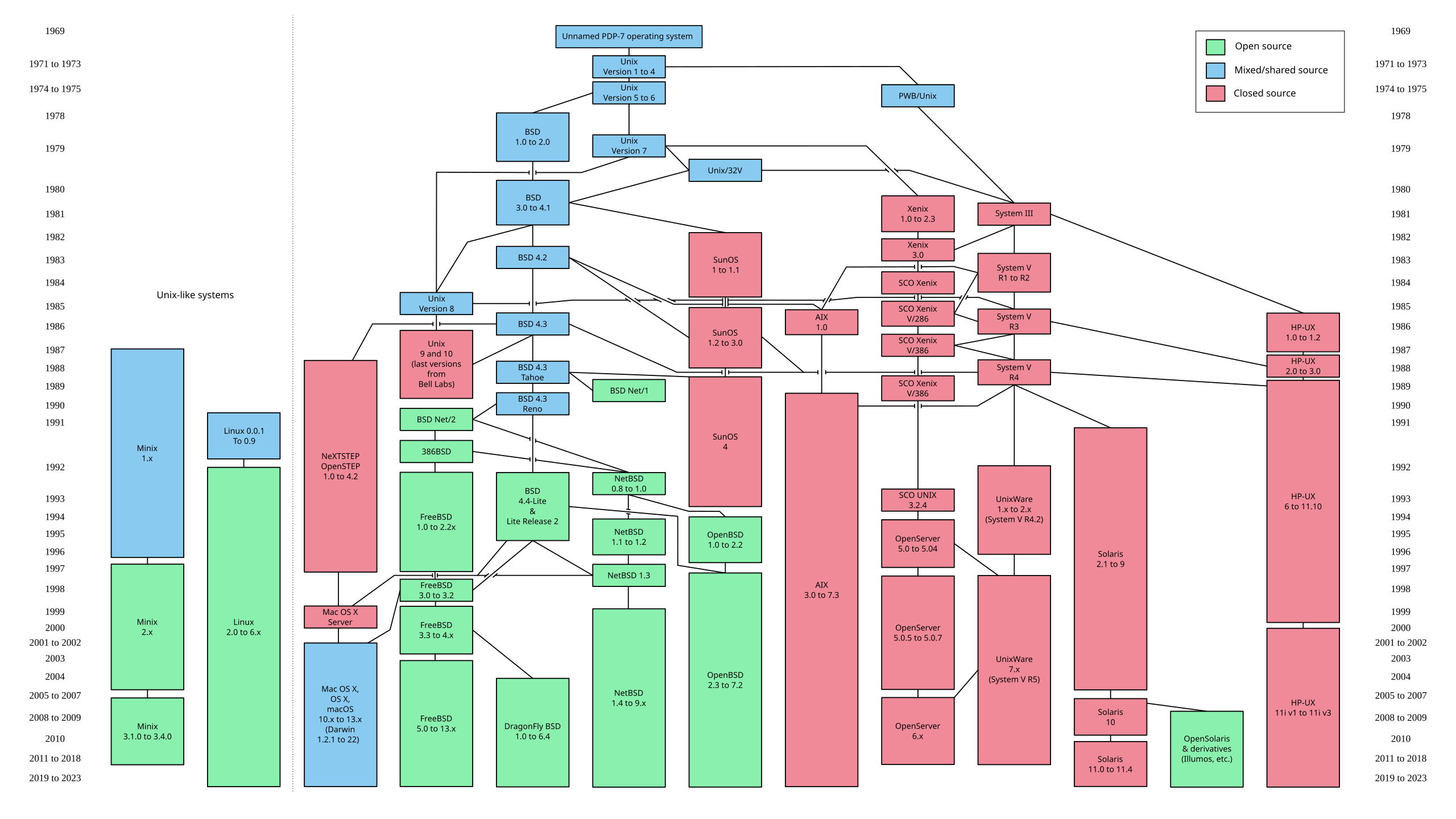

By Eraserhead1, Infinity0, Sav_vas - Levenez Unix History Diagram, Information on the history of IBM's AIX on ibm.com,CC BY-SA 3.0,https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1801948

关于 Wayland 的一些工具之间的关系:

|

|

By Shmuel Csaba Otto Traian, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28029855

By Shmuel Csaba Otto Traian, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31768083

By Shmuel Csaba Otto Traian, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27858390

By Shmuel Csaba Otto Traian,CC BY-SA 3.0,https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27799196

所以通过 DRM 可以在 Linux 下直接操作 Frame Buffer 上,也就是 Direct Rendering Manager。相关的库有:

有了这个就可以在 Linux 上直接做纯 Go 的绘制了,从而消除对 C 遗产的依赖。

2021/01/05 Daily Reading

读了这几篇文章:

- The Right to Read. https://www.gnu.org/philosophy/right-to-read.en.html

- Your Computer Isn’t Yours. https://sneak.berlin/20201112/your-computer-isnt-yours/

- Pirate Cinema. https://craphound.com/pc/download/

注意到了这两个跟剪贴板相关的项目:

看起来他们开发这两个项目的时间跟我开发 midgard 的时间非常接近,不过大家都走了很不同的路线:

- pcopy 着重剪贴板本身,比如有剪贴板的密码保护,多种剪贴板、WebUI 等特性

- pggopy 注重设备间同步的安全性,有各种密钥配置,但功能非常简单,只支持文本

我开发的 midgard 的则主打这些特性:

- 多设备间自动同步(剪贴板回写),不需要敲命令

- 能够查询同时在线的设备

- 不仅支持文本,还支持图片的同步

- 支持对剪贴板中的内容创建公开的 URL

- 支持剪贴板中的代码转 Carbon 图片

- 支持键盘快捷键

- …

2020/12/31 Daily Reading

- A History of the GUI. http://www.cdpa.co.uk/UoP/Found/Downloads/reading6.pdf, https://www.readit-dtp.de/PDF/gui_history.pdf

- History of the graphical user interface. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_graphical_user_interface

- Algebraic Effects for the Rest of Us. https://overreacted.io/zh-hans/algebraic-effects-for-the-rest-of-us/

- What does algebraic effects mean in FP? https://stackoverflow.com/questions/49626714/what-does-algebraic-effects-mean-in-fp

- A Distributed Systems Reading List. https://dancres.github.io/Pages/

- Tutte Embedding for Parameterization. https://isaacguan.github.io/2018/03/19/Tutte-Embedding-for-Parameterization/

- Commentary on the Sixth Edition UNIX Operating System. http://www.lemis.com/grog/Documentation/Lions/index.php

- Personal knowledge management beyond versioning. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2362456.2362492

- The Plain Text Life: Note Taking, Writing and Life Organization Using Plain Text Files. http://www.markwk.com/plain-text-life.html

- Post-Evernote: How to Migrate Your Evernote Notes, Images and Tags Into Plain Text Markdown. http://www.markwk.com/migrate-evernote-plaintext.html

- Five Levels of Error Handling in Both Python and JavaScript. https://dev.to/jesterxl/five-levels-of-error-handling-in-both-python-and-javascript-13ok

2020/12/30 Daily Reading

- The UNIXHATERS Handbook. http://web.mit.edu/~simsong/www/ugh.pdf

- Why are video games graphics (still) a challenge? Productionizing rendering algorithms. https://bartwronski.com/2020/12/27/why-are-video-games-graphics-still-a-challenge-productionizing-rendering-algorithms/

- BPF and Go: Modern forms of introspection in Linux. https://medium.com/bumble-tech/bpf-and-go-modern-forms-of-introspection-in-linux-6b9802682223

- Systems design explains the world: volume 1. https://apenwarr.ca/log/20201227

- Error handling guidelines for Go. https://jayconrod.com/posts/116/error-handling-guidelines-for-go

- The Missing Semester of Your CS Education. https://missing.csail.mit.edu/

- Build your own React. https://pomb.us/build-your-own-react/

2020/12/27 Concurrency Patterns

Fan-In multiplexes multiple input channels onto one output channel.

|

|

Fan-Out evenly distributes messages from an input channel to multiple output channels.

|

|

Future provides a placeholder for a value that’s not yet known.

|

|

Sharding splits a large data structure into multiple partitions to localize the effects of read/write locks.

|

|

2020/12/26 Stability Patterns

Circuit Breaker automatically degrades service functions in response to a likely fault, preventing larger or cascading failures by eliminating recurring errors and providing reasonable error responses.

|

|

Debounce limits the frequency of a function call to one among a cluster of invocations.

|

|

Retry accounts for a possible transient fault in a distributed system by transparently retrying a failed operation.

|

|

Throttle limits the frequency of a function call to some maximum number of invocations per unit of time.

|

|

Timeout allows a process to stop waiting for an answer once it’s clear that an answer may not be coming.

|

|

2020/12/25 LBRY

一个去中心化的视频平台,似乎是 YouTube 的竞争对手?

2020/12/15 “Worse is Better”

偶然间读到了一篇文章的节选片段《The Rise of Worse is Better》,这篇文章的作者 Richard 围绕为什么 C 和 Unix 能够成功展开了反思。这篇文章中聊到了几个软件设计的四大目标简单、正确、一致和完整。其中围绕四个目标发展出了两大很有代表性的流派: MIT 流派和 New Jersey 流派(贝尔实验室所在地)。MIT 流派认为软件要绝对的正确和一致,然后才是完整,最后才是简单;而一并“讽刺”了 New Jersey 流派反其道而行之的做法,他们将简单的优先级设为最高,为了简单甚至能够放弃正确。换句话说,软件的质量(受欢迎的程度)并不随着功能的增加而提高,从实用性以及易用性来考虑,功能较少的软件反而更受到使用者和市场青睐。

所以你看到为什么总是有些人总是抱怨 Go 这也不行那也不行,这也没有那也没有了。因为来自贝尔实验室的 Rob Pike 就是一个彻彻底底的 New Jersey 流派中人。所以总结起来 Go 的特点就是:

- 简单

- 非常简单

- 除了简单就是简单

然后围绕 Worse is Better 还有好几篇后续文章:

- 原始文章: Richard P. Gabriel. The Rise of Worse is Better. 1989. https://www.dreamsongs.com/RiseOfWorseIsBetter.html

- 后续1: Nickieben Bourbaki. Worse is Better is Worse. 1991. https://dreamsongs.com/Files/worse-is-worse.pdf

- 后续2: Richard P. Gabriel. Is Worse Really Better? 1992. https://dreamsongs.com/Files/IsWorseReallyBetter.pdf

- 后续3: Richard P. Gabriel. Worse is Better. 2000. https://www.dreamsongs.com/WorseIsBetter.html

- 后续4: Richard P. Gabriel. Back to the Future: Worse (Still) is Better! Dec 04, 2000. https://www.dreamsongs.com/Files/ProWorseIsBetterPosition.pdf

- 后续5: Richard P. Gabriel. Back to the Future: Is Worse (Still) Better? Aug 2, 2002. https://www.dreamsongs.com/Files/WorseIsBetterPositionPaper.pdf

所以你更倾向于哪个学派?

2020/12/13 Proebsting 定律

今天额外读了一篇论文,虽然跟 Go 没有直接关系,但我觉得对理解目前 Go 语言的现状是有一定启发意义的,所以来分享一下。这篇论文叫做 “On Proebsting’s Law”。

我们都知道 Moore 定律说集成电路上晶体管数量每 18 个月番一番,但这篇论文则研究并验证了所谓的Proebsting 定律: 编译器优化技术带来的性能提升每 18 年番一番。Proebsting 定律是在 1998 年提出的,当时的提出者 Todd Proebsting 可能只是在开玩笑,因为他建议编译器和编程语言研究界应该减少对性能优化的关注,而应该更多的关注程序员工作效率的提升。

现在我们来事后诸葛亮评价这一建议就能发现其实这并不是无道理的: Go 语言的编译器虽然经历过几大版本的优化,但其使用的技术并不够 fancy,相反而是很传统且中规中矩的优化技术。然而这并不影响 Go 语言的成功,因为它尝试解决的正是程序员的工作效率:

- 通过避免循环以来而极大的减少了程序员等待编译的时间

- 非常简洁的语言设计与特性极大的减少了程序员思考如何使用语言的时间

- 向前的兼容性保障几乎彻底消除了因为版本升级给程序员带来的迁移和维护时间

- 论文地址: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.29.434&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Proebsting’s Law: http://proebsting.cs.arizona.edu/law.html

2020/12/12 Telegram Bot

因为欧洲疫情依然很糟糕,所以现在甚至于想去苹果店购物都要提前预约。因为最近急需要去苹果店一次,又苦于刷不到可用的预约位置,刚刚顺手就糊一个工具来检查,当预约可用时给telegram发送一条提醒消息。工具地址: https://changkun.de/s/apreserve

用 Go 和 telegram 进行交互没有任何难度:

- 从 botfather 创建一个 bot

- 获得这个 bot 的 token 以及跟它对话的 chatid

- 于是可以处理消息了

- BotFather: https://t.me/botfather

- Tg bot API Go bindings: https://github.com/go-telegram-bot-api/telegram-bot-api

|

|

2020/12/10 Apple Silicon

Go在darwin/arm64上的编译性能怎么样?我很不严谨的粗略比较了Intel Mac 和 M1 Mac 的 Go 编译性能。这个编译报告由如下指令生成:

$ go build -gcflags=‘-bench=bench.out’ -a $ cat bench.out

其中-a用于禁用编译缓存。

MacBook Air (M1, 2020), Apple M1, 16 GB:

|

|

Mac mini (2018), 3 GHz 6-Core Intel Core i5, 8 GB 2667 MHz DDR4:

|

|

2020/12/09 弃用 ioutil

ioutil 将在 Go 1.16 中被彻底弃用,虽然由于兼容性保障这些 API 还会继续存在,但不再被推荐使用了。那么问题来了,我们应该用什么?这是 ioutil 包所有的 API:

|

|

1.16 中取而代之的与之对应的 API:

|

|

总结起来就是三点:

- Discard, NopCloser, ReadAll 挪到了 io 包中

- ReadDir, ReadFile, WriteFile 挪到了 os 包中

- TempDir, TempFile 更名为了 MkdirTemp, CreateTemp 并挪到了 os 包中

2020/12/07 测试 io/fs 的实现

io/fs 越来越近了 功能很好但我们怎么才能测试它呢?testing/fstest 中有一个函数可以做到这件事情。

|

|

2020/12/01 回顾异步抢占

你确定你看懂异步抢占了吗?今天跟曹大@Xargin 交流起异步抢占的流程里被中断的 G 是如何恢复到之前的执行现场时才发现对异步抢占的理解还不够全面。在《Go 语言原本》中是这样描述异步抢占的: 不妨给正在运行的两个线程命名为 M1 和 M2,抢占调用的整体逻辑可以被总结为:

- M1 发送中断信号(

signalM(mp, sigPreempt)) - M2 收到信号,操作系统中断其执行代码,并切换到信号处理函数(

sighandler(signum, info, ctxt, gp)) - M2 修改执行的上下文,并恢复到修改后的位置(

asyncPreempt) - 重新进入调度循环进而调度其他 Goroutine(

preemptPark和gopreempt_m)

这个总结并不完全正确,因为它并没有总结清楚 preemptPark 和 gopreempt_m 这两者之间的区别。这周我们来简单补充一下异步抢占的整体行为:

假设系统监控充当 M1,当系统监控发送中断信号后,会来到 asyncPreempt2:

|

|

但最终会选择 preemptPark 还是 gopreempt_m 呢?sysmon 调用 preemptone 的代码中发出的异步抢占并不会为 G 设置 preemptStop 标记,从而会进入 gopreempt_m 的流程,而 gopreempt_m 最终会调用 goschedImpl 将被抢占的 G 放入全局队列,等待日后被调度。

那么另一半(preemptPark)呢?当我们仔细查看 preemptPark 的实现则会发现,被抢占的 G 其实并没有被加入到调度队列中,而是直接就调用了 schedule:

|

|

那这时被抢占的 G 怎样才会恢复到调度循环呢?原来 gp.preemptStop 为 true 的分支发生在 GC 需要时(markroot)通过 suspendG 来标记正在运行的 G(gp.preemptStop = true),再发送抢占信号(preemptM),返回被中断 G 的状态。当 GC 的标记工作完成,抢占结束后,在将这个状态传递并调用 resumeG,最终 ready 并恢复这个被中断的 G:

|

|

2020/11/26 错误提案的总结

错误处理有多无聊 看看这个非常相近的总结就知道了

https://seankhliao.com/blog/12020-11-23-go-error-handling-proposals/

2020/11/15 数据竞争和内存模型

这段代码有 data race 吗?

|

|

昨天提交的一个 issue 似乎指出了目前 Go 内存模型中的一个错误。进一步阅读:

- https://golang.org/issue/42598

- https://golang.org/issue/37355

- https://go-review.googlesource.com/c/go/+/220419/

- https://reviews.llvm.org/D76322

2020/11/14 关于 Go 错误处理的进一步看法

续: 很多人不满错误处理的原因在我看来是没有耐心去理解 Go 里处理问题的方式,Jonathan 总结得到的一个重要教训就是错误本身就是领域特定的,有些领域关注如何更好的追踪错误来源,但堆栈信息本身有时候也不那么有用;有些领域关注如何更加灵活的对多个错误信息进行整合,但很多人可能只想把正常逻辑给写对了然后统一扔一个错误出去等等,后续他的QA中还提到不建议使用xerrors等。(不那么)显然,只有针对问题本身给出的方案才是最好的,开发者应该静下心来思考怎么对某个具体问题设计错误处理,吐槽什么语法层面有没有 try/catch 、 if err 满天飞丑到哭泣就跟讨论泛型用什么括号一样没有意义且浪费生命。

2020/11/13 Go 1.13 错误值提案的遗憾

今天的 GopherCon2020 上,Go 1.13 错误值提案的作者事后提及他对目前错误格式化的缺失表示遗憾,而且在未来很长的好几年内都不会有任何进一步改进计划。对此他本人给出的原因之一是对于错误处理这一领域特定的问题,在他的能力范围内实在是无法给出一个令所有人都满意的方案。尽管如此,在他演讲的最后,还是给出了一些关于错误嵌套的建议,即实现 fmt.Formatter,下面给出了一个简单的例子。

|

|

2020/11/09 macOS 下获取时钟频率

macOS 下获取 CPU 时钟频率的方法

|

|

2020/11/08 Detach A Context

如何构造一个保留所有 parent context 所有值但不参与取消传播链条的 context?

|

|

2020/11/07 工具 bench

新写了一个叫做 bench 的工具,主要对进行基准测试中的实践进行了整合与封装。

用法参见: https://golang.design/s/bench

2020/11/05 空间换时间

有什么办法能够让这两个函数跑得更快吗?

|

|

这里介绍一个很平凡的优化方案: lookup table + 线性插值:

|

|

基准测试显示,优化后的运行时性能提升约为 98%。 name old time/op new time/op delta Linear2sRGB-6 6.38µs ± 0% 0.14µs ± 0% -97.87% (p=0.000 n=10+8)

2020/11/04 传值与传指针

猜猜 vec1 和 vec2 实现的 add 哪个性能更好?

|

|

答案是传值更快。原因是内联优化,而非很多人猜测的逃逸。原因是指针实现的方式虽然返回了指针,但却只是为了能够支持链式调用而设计的,返回的指针本身就已经在栈上,不存在逃逸一说。测试结果:

|

|

一个实际的例子是,将传指针改为传值方式在一个简单的光栅器中带来了 6-8% 的性能提升(见 https://github.com/changkun/ddd/commit/60fba104c574f54e11ffaedba7eaa91c8401bce4)。

除此之外,我们可能会问,如果没有内联的话,还是传值更快么?我们可以试着给两个加法方法增加 //go:noinline 编译标记,最终的结果(old)跟有内联的结果(new)对比如下所示:

|

|

那么问题又来了,在没有内联的情况下,为什么指针更快呢?请阅读 https://changkun.de/blog/posts/pointers-might-not-be-ideal-for-parameters/

2020/11/03 Timer 的一枚优化

Go 1.14 中,time.Timer 曾从全局堆优化到了 per-P 堆,并在调度循环进行任务切换时,独自负责检查并运行可被唤醒的 timer。但在当时的实现中,偷取过程并没有检查那些位于正在执行(与 M 绑定)的 P 上的 timer 堆,即如果某个 P 发现自己无事可做,即便其他 P 上的 timer 需要被唤醒,这个无事可做的 P 也会进一步休眠;好在该问题在 1.15 得到了解决。但这就万事大吉了吗?

可惜的是,per-P 堆方法的本质仍然上是在依赖异步抢占来强制切换那些长期霸占 M 的 G,进而 timer 总能在有界的时间内被调度。但这个界的上限是多少?换句话说,time.Timer 的唤醒延迟到底有多高?

显然,现在异步抢占的实现依赖系统监控,而系统监控的唤醒周期是 10 至 20 毫秒级的,这也就意味着在最坏情况下,将对一些对实时性要求极高的服务(如实时流媒体)会产生严重的干扰。

在即将到来的 1.16 中,一项新的修复将这种数十毫秒级的延迟直接干到了微秒级,非常的 exciting。下面的基准测试展示了如何系统的通过平均延迟以及最坏延迟两个指标对 timer 的延迟进行量化,并附上了进一步改进后的 timer 延迟与 1.14, 1.15 中结果的对比。

|

|

2020/11/02 运算符的优先级

今天来聊聊 C 语言算符优先级设计的历史吧。在C语言之父 Dennis Ritchie 的回忆邮件 (https://www.lysator.liu.se/c/dmr-on-or.html) 中曾提起过为什么今天 C 语言里有些运算符的优先级是 “错误” 的(比如,& 和 && 的优先级都比 == 低,但 Go 的 & 比 == 高)。

从类型系统的角度考虑,if while 环境下算符参与的表达式的最终结果是布尔值。对于位运算符 & 而言,位算符的输入是数值、输出是数值,而 == 则必须接受两个数值才能得到一个布尔值,因此 & 的优先级必须高于 ==。同样的原因 == 必须高于 && 。

可是,早年的 C 并没有 & 和 && 或者 | 和 || 算符的区分,只有 & 和 |。那时 & 在 if 和 while 语句中被解释为逻辑算符,并在表达式中作为位运算进行解释。所以能被视为逻辑算符的 & 被设计为低于 == 算符,例如 if(a==b & c==d) 将先执行 == 再判断 &。

后来在引入 && 作为逻辑算符将这种二义行为进行拆分时,C 已经有一定用户了,即便将 & 其优先级提升到 == 之前更好,也已经无法再做这种级别的改动了,因为这将在没有任何感知的情况下破坏现有用户的代码行为(b&c 将先取得某个值,并依次与 a、d 做 == 比较),只能无奈的将 && 的优先级放到 & 之后,却不能对 & 做任何修正(显然 Go 作为后继,& 和 && 的区别已经司空见惯,也就很容易做出正确的设计)。但 Go 的设计就一直都很完美无暇吗?最近就有一个反例。

在即将到来的 Go 1.16 中同样也有这样的“历史插曲”: 在引入 io/fs 后,重新调整的 os 包中,增加了一个新的 File.ReadDir 方法,功能与已有的 File.Readdir (注意字母大小写)几乎完全一致,这种功能、名字都高度相似的情况,似乎与 Go 注重特性垂直独立的设计哲学相违背,删除老旧的 File.Readdir 固然能够让用户更加直观的理解应该使用哪个 API,但实际上这与当年的 C 面临的是同样的困境,即为了兼容性保障,任何破坏性的改动都是不可取的。他们最终都得到了保留。

2020/11/01 t.Cleanup 的嵌套问题

早在 Go 1.14 中,testing 包就引入过一个 t.Cleanup 的方法,允许在测试代码中注册多个回调函数,并以注册顺序的逆序在测试结束后被执行。从其实现来看,你能在一个 Cleanup 里注册的回调中,嵌套注册另一个 Cleanup 吗?现在(1.15)还不能。

|

|

2020/10/31 初窥 io/fs

在即将到来的 Go 1.16 中,我们将允许将资源文件直接嵌入到编译后的二进制文件中。它是怎么实现的?嵌入后的文件表示是什么? 从更广泛的问题抽象出发,我们需要一个 in-memory 的文件系统。于是这又进一步启发我们对文件系统抽象的思考,文件系统的所需最低要求是什么?文件系统承载的文件又必须要求哪些操作?所有这些问题的答案都浓缩在了这里。

io/fs.FS:

|

|

embed.FS:

|

|

2020/10/30 获取 Goroutine ID

可能是具有 Go 1 兼容性保障的全版本获取 gorountine ID 的最快的实现

|

|

2020/10/19 基准测试的番外

很多人都编写过 Benchmark 测试程序,在 Go 夜读第 83 期 对 Go 程序进行可靠的性能测试 (https://talkgo.org/t/topic/102) 分享中也跟大家分享过如何利用 benchstat, perflock 等工具进行严谨可靠的性能测试。在那个分享中也曾简单的讨论过基准测试程序的测量方法及其实现原理,但由于内容较多时间有限对性能基准测试的原理还不够深入。因此,今天跟大家进一步分享两个未在第 83 期覆盖,但在进行某些严格测试时较容易被忽略的细节问题:

- 进行基准测试时,被测量的代码片段会的执行次数通常大于 b.N 次。在此前的分享中我们谈到,testing 包会通过多次运行被测代码片段,逐步预测在要求的时间范围内(例如 1 秒)能够连续执行被测代码的次数(例如 100000 次)。但这里有一个实现上的细节问题: 为什么不是逐步多次的累积执行被测代码的执行时间,使得t1+t2+…+tn ≈ 1s,而是通过多次运行被测代码寻找最大的 b.N 使得 b.N 次循环的总时间 ≈ 1s?原因是逐步运行基准测试会产生更多的测量系统误差。基准测试在执行的初期通常很不稳定(例如,cache miss),将多个增量运行的结果进行累积会进一步放大这种误差。相反,通过寻找最大的 b.N 使得循环的总时间尽可能的满足要求范围的连续执行能够很好的在每个测试上均摊(而非累积)这一系统误差。

- 那么是不是可以说 testing 包中的实现方式就非常完美,作为用户的我们只需写出基准测试、在 perflock 下运行、使用 benchstat 消除统计误差后我们不需要做任何额外的操心了呢?事情也并没有这么简单,因为 testing 包的测量程序本身也存在系统误差,在极端场景下这种误差会对测量程序的结果产生相当大的偏差。但要讲清楚这个问题就需要更多额外的篇幅了,所以这里再额外分享了一篇文章 Eliminating A Source of Measurement Errors in Benchmarks(https://github.com/golang-design/research/blob/master/bench-time.md),以供你进一步阅读。在这篇文章里你可以进一步了解这种测量程序内在的系统测量误差是什么,以及当你需要对这种场景进行基准测试时,几种消除这类误差源的可靠应对方案。

2020/10/01 Hello

Hello world!